From Good to Great: Enhancing Your Story with a Strong Dramatic Core

How to keep your readers engaged with a clear central dramatic question

In my brief series of posts about why your pitches fail to land an agent or publisher, I mentioned the importance of understanding your central dramatic question. (Spoiler: If you can’t state your central dramatic question succinctly, you’ll have difficulty writing your synopsis.)

A couple of readers asked about how to incorporate that information into the actual story, so today, I’ll shed more light on the topic.

The Problem—Unclear Central Dramatic Question

The central dramatic question is a critical element of genre fiction, providing focus and direction to the narrative. This is the primary question around which the narrative revolves. It is what the story ultimately aims to answer by the end.

Will the young prince slay the dragon?

Will the detective solve the crime before the villain kills again?

Will the teenagers escape the slasher?

Unfortunately, in many of the stories I edit—and yes, even in some of the self-published comics I read—this question is muddled, lazy, or absent altogether.

You’d think this would be easy. The general idea you have, the thing driving your main character, is pretty much the central dramatic question. But there are so many ways for it to get lost as you write the story.

Sure, it’s in there somewhere, but if it’s unclear or if the characters go on too many unrelated tangents, you risk losing readers.

I also spot problems with the central dramatic question and how it ties to the promise of the premise. For example, if readers understand the question as being, “Will the prince slay the dragon?” then there’s an expectation that a dragon will play prominently in the story. If not, you’re not giving the reader what you promised.

If you can’t state your central dramatic question clearly, you’ll most likely have difficulty writing the story. And if you’ve written the story but you still can’t state the question clearly, you’ll never land an agent. Without a clear central dramatic question, your 30-second elevator pitch will never get you to the next floor. Without a clear central dramatic question, you don’t have a foundation for your marketing, either.

We sometimes get so focused on other aspects of storytelling, or we fall so in love with a new idea, that we forget to focus on this crucial element, then the story goes off course with each new idea we have, and then readers are left with another “oh, that could’ve been great if…” story.

Why the Central Dramatic Question Matters

The central dramatic question is crucial because it offers:

Narrative Focus — It defines the core conflict and goal. If your story is well told, it ensures that all story elements revolve around a central theme or objective.

Character Motivation — It directly ties to the protagonist's goals (and to the journey itself) and provides a clear framework for their development and growth.

Audience Engagement — By posing a compelling question, it sets your readers’ expectations. They know what they’re getting into before they read your book. And if you’ve set it up correctly and continue to revolve the story around your question, it keeps readers invested… they’ll want to see how the characters confront and resolve the narrative’s main challenge.

The question is important for comic series, too. For a series, there should be a clear narrative question for the series and for each issue. Your hero needs some goal to attain within each chapter. In other words, each issue needs to have a beginning, middle, and end, and the narrative question helps drive the narrative forward… it gives the reader something to hook into.

Explicit vs. Implied Central Dramatic Questions

Some confusion around this topic comes up when it appears as if some books, movies, or comics don’t have a central narrative question. At least, not one that can be easily labeled as such.

But that’s incorrect. It’s not that some stories don’t have the question, it’s that the question is implied instead of explicit.

Let’s look at some examples.

Examples of Explicit Narrative Questions

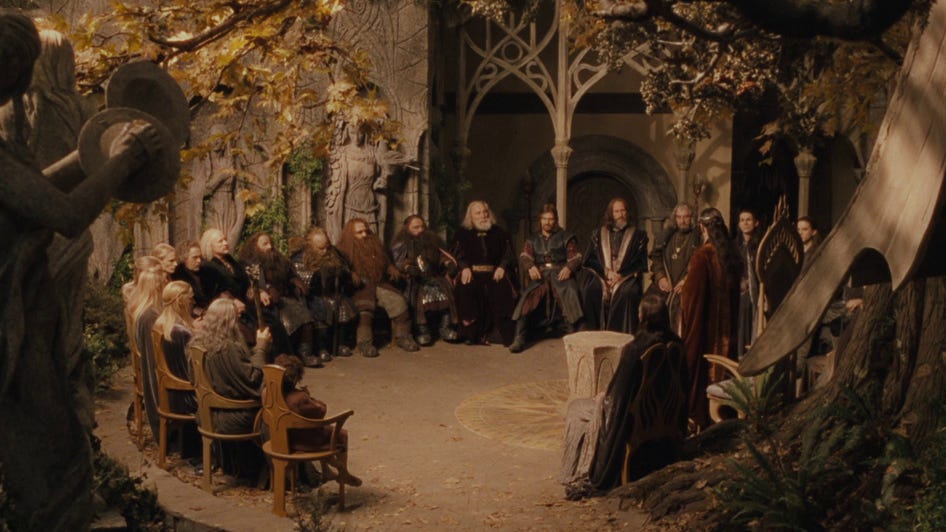

In the Lord of the Rings series, the question is explicit. Will Frodo succeed in destroying the one ring?

This explicit question is posed at the Council of Elrond. It frames Frodo's mission and sets the stakes for the entire series. Aside from some character moments and subplots here and there, everything that happens after this question is posed makes the reader question if they’ll succeed.

Notice that the question is posed in the second chapter of Fellowship of the Ring. In the movies, it happens about midway through the first film, so about a quarter of the way into the series. I’ll get to why this is important in a moment.

The central dramatic question is also explicit in The Hunger Games: Will Katniss Everdeen survive the Hunger Games?

Just by asking that question, you have an idea of what the story is about. You can expect to see her tested physically and mentally.

Guess what? Katniss volunteers for the Games in Chapter 2. Again, the question is posed early in the story to hook the reader. It drives the narrative forward almost immediately after we learn a little about the character.

Examples of Implied Narrative Questions

Things are a little different with Dune. Here, the central dramatic question is implied. Can Paul Atreides fulfill his destiny and protect the people of Arrakis from oppression?

Note that the question is never directly stated. The narrative implies this question through prophecy, political intrigue, and Paul's actions, subtly guiding the plot's progression. The more you read, the more you feel the tension mounting, and it all revolves around fulfilling his destiny.

Another example of an implied dramatic question is Stephen King’s The Shining. Will the Torrence family survive the winter at the Overlook Hotel? Rather than directly stating that survival is at stake, the story lets the audience pick up on the foreboding atmosphere, the hotel's sinister nature, and Jack’s instability, all of which imply that survival is uncertain.

Although these are implied dramatic questions, note that they’re felt early in the story:

In Chapter One of Dune, Paul is given the Gom Jabbar test, which tests his ability to withstand immense pain and fear, thereby introducing readers to his potential as the prophesied Kwisatz Haderach.

In chapter one of The Shining, we already catch glimpses of Jack’s temper and troubled nature. When combined with the understanding that they’ll be cut off from the rest of the world all winter, we can sense the trouble brewing.

Where Writers Often Fail

Without an effective central dramatic question, stories may feel meandering, as if they lack direction. Characters’ actions are meaningless, and readers will struggle to understand or care about the stakes, diminishing their emotional investment.

In the stories I edit, there are three ways stories falter when it comes to the central dramatic question:

The story doesn’t actually follow the question that was set up in the first act. Some scenes seem to relate, while others feel inserted almost at random.

It’s unclear, making the story lack direction and purpose, which reduces tension and suspense.

It’s stated too late, which leads to early scenes that feel confusing, bloated, or unnecessary. This leads to pacing problems and gives the reader an excuse to stop reading.

When I see these problems, they’re usually (but not always) from:

Pantsers who discovered their story as they wrote it but didn’t go back to connect all the dots. They didn’t smooth out the rough edges to ensure most (if not all) of the scenes point toward the solution of the question.

Comic writers who write and publish their stories issue by issue instead of understanding the entire series before they publish. Sometimes, a single issue has a strong dramatic question, but from issue to issue, there’s no clear narrative or goal for the protagonist.

Those are two somewhat hasty generalizations, but that’s what I’ve seen.

Solutions

It’s important to keep your central dramatic question strong, consistent, and effective. Here are some strategies to keep in mind:

1. Write Down the Dramatic Question

For most aspiring or intermediate writers, I’d go so far as suggesting that you shouldn’t start writing your first draft unless you can clearly write your central dramatic question. Yes, it might change as you’re writing, especially if you’re a pantser, but if you don’t have a concise question, you’ll likely stray off-target.

If you’ve already written your story but can’t write the central dramatic question concisely, then the story is likely too muddled or it meanders too much. Consider revising your story so it’s more focused.

Regardless of how you get there, the question needs to match the story you write and vice versa.

2. Early Introduction

Introduce the question within the first act, setting up the main conflict and stakes early to captivate the audience. For implied questions, you must lay the groundwork early and often by putting the characters in situations that support the narrative goal.

The inciting incident is often tied directly to the introduction of the central dramatic question. The inciting incident is the event or decision that ignites the plot and propels the protagonist into the main storyline. This scene includes something that disrupts the status quo and forces the protagonist to take action, setting the narrative in motion. Will they succeed?

I usually recommend newer writers use the three-act structure, but I don’t typically suggest setting goals for when certain things happen in a story. However, if the inciting incident doesn’t happen at or around the 10-15% mark, I start to feel unsure about the narrative. If I’m closing in on 20% or more, I’m disengaging. And if I feel that way, you can bet your reader will.

If you’ve written the novel already, simply divide your word count by ten. For example, if you have an 80,000-word novel, ten percent is 8,000 words. So your question should become obvious to readers at roughly that spot.

For comics, it’s not word count but page total. If your graphic novel is 250 pages, your question should be obvious by around page 25. For comic writers, I suggest you be more strict with the 10% guideline and maybe even err on the side of including that incident too soon instead of too late. (If you’re writing single issues within a series, your central dramatic question for later issues might come as soon as page one, or they might even be tied to the cliffhanger from the previous issue.)

3. Clarity and Relevance

Ensure the question is clearly connected to the protagonist's goals in the story and the central conflict he faces. It should resonate with his desires and challenges. In other words, inspect every scene, every action. Ask yourself: does this decision revolve around the question?

4. Incorporate Tension

Embed elements of suspense and uncertainty within the central dramatic question to maintain tension, compelling readers to anticipate the resolution. As I stated earlier, in many ways, the central dramatic question is tied to or hints at the promise of the premise.

If the question is whether she’ll survive the night and save her kids from the vampires, there’s a level of uncertainty built into the question itself. We know that at some point, her kids will be in danger and that she or one of the kids will be on the brink of being bitten. You must give your readers those moments.

5. Reflect Throughout the Story

Revisit and reinforce the dramatic question at key points, ensuring the question drives the narrative and influences character decisions and transformations. Doing this ensures that your story never wanders off track.

This is not an excuse to ignore the need for organic storytelling. Your lead’s actions and decisions need to lead to the next event. Don’t just plop in a plot point because you need to get your character back on track.

Look, I get it. You have this idea for an epic battle scene or an incredible twist your readers won’t see coming. But if a scene is not closely tied to the central question and it doesn’t grow from previous moments in the story, your incredible scene won’t have real stakes, which means you run the risk of losing the reader.

6. Enhance with Subplots

Subplots can add layers to the narrative, providing depth and complexity to the main storyline. The best subplots can explore themes and issues that complement or contrast with the central dramatic question, providing an even richer storytelling experience.

When subplots are handled with style, they enhance the characters in a way that supports the dramatic question.

For example, in The Lord of the Rings, Aragorn’s relationship with Arwen serves as a subplot that enriches the larger narrative. It reflects themes of duty, sacrifice, and hope. These elements are central to the primary quest to destroy the One Ring and defeat Sauron. Their relationship also influences Aragorn’s arc, supporting his path to becoming king, which is critical to resolving the dramatic question.

So while a scene with Aragorn and Arwen talking quietly doesn’t directly help answer “Will Frodo destroy the One Ring?” it does develop his character in a way that ties directly to the key narrative.

Exercises

If you haven’t already, take a moment to write your central dramatic question for the story you’re working on. Work at it until you can write it clearly.

If you’ve already written your story, work through every scene to spot those moments that don’t tie back to the question.

You can also list your main characters and their primary goals in the story. Make note of how their goals support or contradict one another (conflict) and whether those goals are in some way tied to the central dramatic question.

Summary

A well-crafted central dramatic question, whether it’s explicit or implied, anchors a story, providing focus, engagement, and meaning. By clearly defining this question early in your narrative and weaving it throughout, you ensure cohesive story development that captures and holds the reader's interest.

If you found value in this post, please like and comment on Substack, and also share it with other writers.